Executive summary

- “Retaliatory Tariffs” increases the growth downside risks. Weak consumer sentiment could translate to lower spending patterns.

- If growth weakness substantially to the extent US demand / spending deteriorates significantly, stagflation risk could rise.

- US equity markets which have seen very strong returns in 2023 and 2024 could mean revert this year.

- Ex-the US, domestic policy may turn more supportive. Asian central banks are adopting an increasingly accommodative stance (given their benign inflation outlook). This is supportive for the region’s fixed income duration-related plays.

- Gold could benefit from safe-haven demand.

- Longer-term, there will be relative winners and losers. Some countries will be incentivised to accelerate the growth of the domestic share of their economy – making them less susceptible to global shocks.

- Amid increased de-globalisation forces, we are likely to see other (ex-US) trading (and capital) blocs emerging.

Will “Liberation Day” tariffs spark a Smoot-Hawley re-run1?

Are the reciprocal tariffs touted by President Trump as “Liberation Day” tariffs – aimed at easing trade deficits with its trading partners, to usher in the “Golden Age of America” positive, or would it instead backfire, dismantle the global trade order, and accelerate de-globalisation pressures?

The announced tariffs turned out to be more aggressive than expected as it contained a baseline duty, with additional penalties for running a trade deficit with the US. This new US so-called “discounted reciprocal” tariff regime is a universal tariff, with an additional levy for countries that have significant tariffs against the US and/or have a large trade deficit with the US.

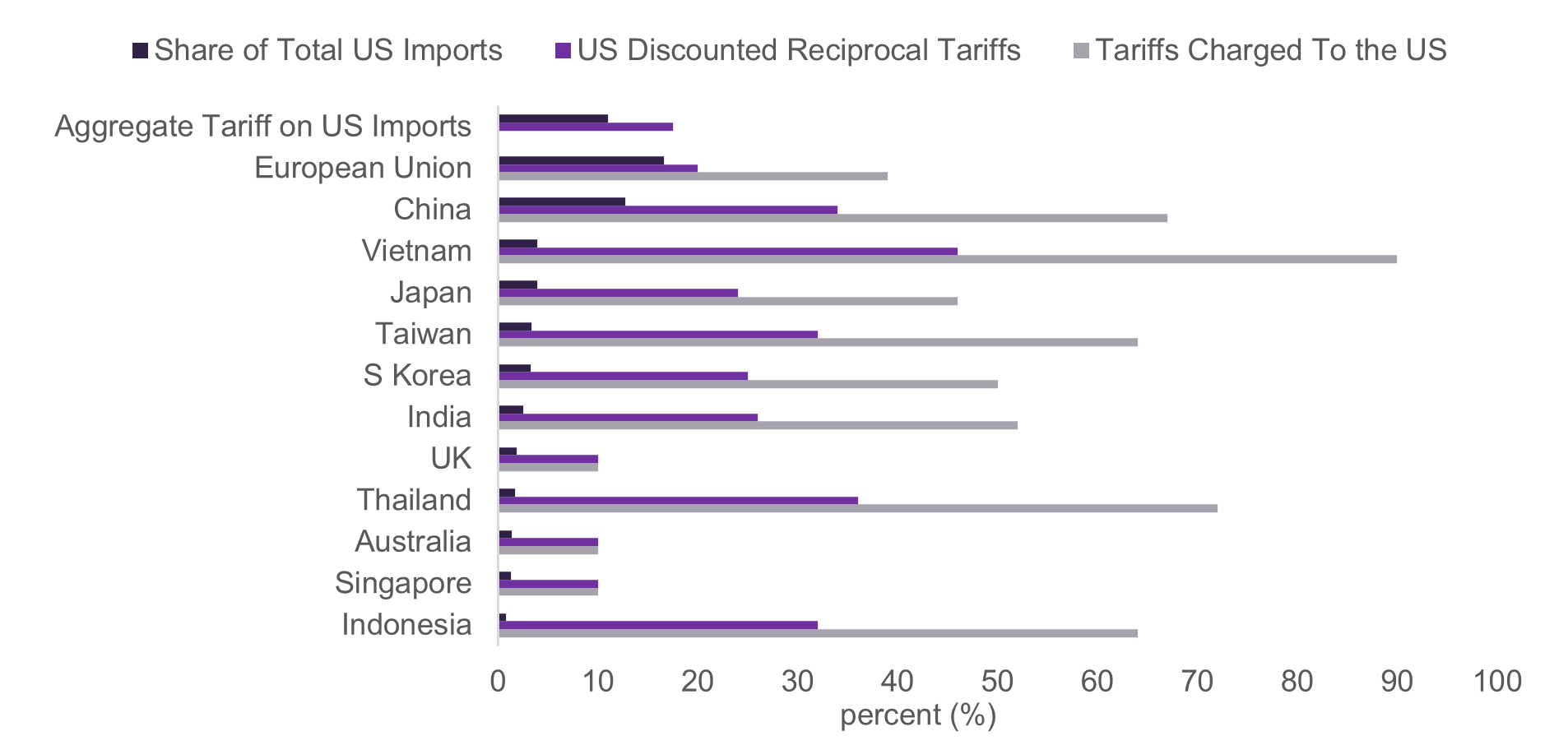

From 5 April, a 10% universal tariff (as announced by the White House), will apply to imports from all countries except Canada and Mexico. Additionally, from 9 April, these trading partners will face an extra tariff equal to half the ratio of the US’ bilateral trade deficit (with the country) relative to US imports from that country. Figure 1 shows the tariff to be faced by the US’ key trading partners (accounting for around 80% of US imports)2.

Figure 1: “US Discounted Reciprocal Tariffs” on selected US trade partners

Source: Fullerton calculations, the White House, and LSEG Datastream, April 2025.

Aggregate US Discounted Reciprocal Tariff is 18%, and total US goods imports to GDP is 11%, Apr 2025.

Macro impacts: stagflationary fears may compress investment returns

In considering potential impacts, the investment “perspective” always makes a huge difference. For example, because of a small import penetration, direct impacts on the US can be modest, but impacts on countries targeted is very different (see Figure 1 above). Vietnam is a great example, where its US trade and tariff burden are large shares of its GDP. Lasting global impacts will also hinge on US-bilateral negotiations to come, as well as potential trade and tariff retaliations.

Fullerton’s calculations3 suggest that the direct impact on US PCE inflation in 2025 could be as high as an extra 1%pts – implying that PCE inflation could potentially hit 3.5% YoY (above the Fed’s March projection of 2.7% YoY). At the same time, US growth is likely to suffer from poor confidence, adverse wealth effects from falling equities, investment spending plans that may be postponed, and further trade-flow retaliations from the rest of the world.

If US consumers react adversely to their lost financial wealth, and higher import prices, then they may cut their spending across all goods and services. US firms may react by scaling back investment plans and job creation. Such an adverse demand spiral could actually pull inflation down, and the Fed’s (March) expectation may be correct that US inflation does fall back to target in 2026 – or sooner (if US growth proves very weak). The Fed already expects US growth to be sub 2% p.a.4 for the next three years, and with its policy rate still well above its assumed longer-term neutral rate of 3%5, its dual mandate may come under significant threat i.e. maintaining full employment and avoiding deflation.

Just as importantly, President Trump’s team will need to make greater efforts to reassure investors and financial markets that US policies – the “3-3-3” agenda – spearheaded by its 3% US real GDP growth target is not collapsing6.

What all these developments may mean for the global investment outlook is that “performance convergence” could become much more rapid and stark. Equity markets like the US where returns have been exceptional for two-years running (i.e. 25% in 2023 and 20247) could mean-revert rapidly. The undershooting investors are already experiencing year-to-date is painful. At the same time, weaker lagging markets (and sectors) may improve, as domestic policy stimulus gives support (i.e. Germany and China). Asian central banks are adopting an increasingly accommodative approach given downside risk to growth while inflation in the region is largely under control. This may prove to be constructive for duration-related Asian local rate fixed income plays.

In China, policymakers are likely to intensify both monetary and fiscal easing to cushion against downside growth risks. On the fiscal front, Beijing is likely to accelerate the implementation of the previously announced stimulus package outlined at the National People’s Congress (NPC)8. This includes increased funding for trade-in subsidies, corporate equipment upgrades, and broader infrastructure investment. Other areas of focus include strengthening household income, improving the social safety net, and encouraging more diverse and sustainable consumption activity (in-line with the longer-term strategic direction to be a more domestically-oriented economy, making it less susceptible to trade-related shocks).

On the monetary side, we anticipate a combination of reserve requirement ratio (RRR) cuts and modest policy rate reductions. Front-end Chinese Government Bond (CGB) yields are expected to remain anchored by monetary easing, while the longer-end may remain steep due to fiscal expansion and increased bond issuance. Should macro conditions deteriorate sharply, or trade tensions escalate further, we expect Beijing to deploy targeted, incremental stimulus to buffer growth. Unlike in 2018, we do not foresee a sharp devaluation of the Renminbi. However, we do not rule out a gradual and managed depreciation of the CNY as part of the broader policy toolkit to absorb external shocks and support competitiveness, especially as export momentum slows.

That said, if US tariffs are much worse than expected, combined with the prospect of “tit-for-tat” trade retaliations, this runs the risk of reducing global trend earnings growth – which would create return expectation headwinds for global equities.

If weaker global growth pulls global inflation down, then the performance gap between bonds and equities could also converge. This is a strategic theme that Fullerton has emphasised for a while, noting that exposure to fixed income, and gold, can give valuable protection to investors’ portfolios from adverse growth shocks.

US-bilateral negotiations to come will be critical, as will potential retaliations from the rest of the world

There are still “relative winners”, as key sources of important US imports (for its domestic manufacturing) – from Canada and Mexico – are now more competitive. The UK, Singapore, and Australia are notable US trading partners where the tariffs are below average (see Figure 1). In contrast, hurdles for many Asian trading partners are higher.

De minimis treatment (i.e. tariff-free personal shipments under $800USD for countries subject to the reciprocal tariff) remains in place, except for China. This keeps US pressure on China significant as it accounts for a substantial share of total de minimis volume. Collectively, President Trump has now hit his campaign suggestion of a 60% tariff on China (including Hong Kong and Macau) – with this shockingly high 34% tariff9 (on top of the 20% enacted in February and March).

Countries can improve their competitive position with the US if they lower the tariffs they charge (the US), which can be done more quickly and easily than pledging to buy more US exports. Larger countries, in particular, may focus more attention on domestic stimulus and productivity gains that can give a significant cushion to trade competitiveness. Countries that have significant global export trade shares are also better placed for effective “tit-for-tat” tariff retaliations. As the US actions represent an extreme push-back against globalisation, events will likely continue to build geopolitical uncertainties e.g stronger and more (ex-US) trading (and capital) blocs could be established.

1 The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (1930) was enacted by the US government to try and protect US growth and jobs by increasing tariffs on US imports by 40-60%. This ultimately resulted in retaliatory tariffs from other countries, contributing to a collapse in global trade, and the Great Depression.

2 The regime is non-“reciprocal” because it captures features beyond the tariffs charged against the US. As the regime is segmented it suggests that the 10% universal tariff is unlikely to be negotiated down, but any additional tariff rate could decline following negotiations (especially if the impacted country lowers its tariffs against the US, or pledges to buy more US exports). There are also product exclusions that may reduce the effective tariff rate i.e. extra tariffs will not apply to existing duties on steel, aluminium, autos, copper, lumber, pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, select minerals, and energy products. That said, there is also potential upside risk from sectoral tariffs not yet announced. Lastly, Trump’s order specifies that if at least 20% of the content is US-origin then the new reciprocal tariff rates apply only to the value of the non-US content of goods.

3 May be subject to change without prior notice.

4,5 Source: FOMC projections, Mar 2025.

6 US real GDP growth is certainly slowing: it was 3.1% in Q3, 2.5% by Q424, and has slipped to a nowcast of 2% at end March 2025 (based on the Dallas Fed’s Weekly Economic Indicator. The Atlanta Fed’s US GDP growth nowcast is much more pessimistic). More importantly, as noted, the Fed stated in March that it now expects US growth to be sub 2% throughout President Trump’s term (i.e. as much as 100bps p.a weaker than what President Trump campaigned upon).

7 Source: LSEG Datastream, Mar 2025.

8 Announced at China’s Mar 2025 NPC.

9 Source: Reuters, Mar 2025.

Important Information

No offer or invitation is considered to be made if such offer is not authorised or permitted. This is not the basis for any contract to deal in any security or instrument, or for Fullerton Fund Management Company Ltd (UEN: 200312672W) (“Fullerton”) or its affiliates to enter into or arrange any type of transaction. Any investments made are not obligations of, deposits in, or guaranteed by Fullerton. The contents herein may be amended without notice. Fullerton, its affiliates and their directors and employees, do not accept any liability from the use of this publication. The information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but has not been independently verified, although Fullerton Fund Management Company Ltd. (UEN: 200312672W) (“Fullerton”) believes it to be fair and not misleading. Such information is solely indicative and may be subject to modification from time to time.

The audio(s) have been generated by an AI app