Executive summary

- China’s growth looks to be behind target.

- As such, infrastructure spending has been cited as a key countercyclical tool to support growth.

- There is appetite for higher infrastructure investments ahead with sufficient funding to finance the earmarked projects.

- Increasingly, the focus is expected to be more on “new economy” infrastructure-related projects in place of “old economy” undertakings.

- Policymakers may however opt to use this growth lever prudently in a measured and targeted manner to avoid the excesses that comes from very aggressive stimulus.

Background

China’s 2022 GDP growth target appears to be behind schedule. One of the levers cited to drive growth ahead is infrastructure spending, but the government is also keen to avoid a situation of excessive debt build-up, especially after the de-leveraging exercise in recent years. Notwithstanding this, infrastructure spending is still looked to as a key countercyclical measure to support growth.

Appetite for increased infrastructure spend ahead is high

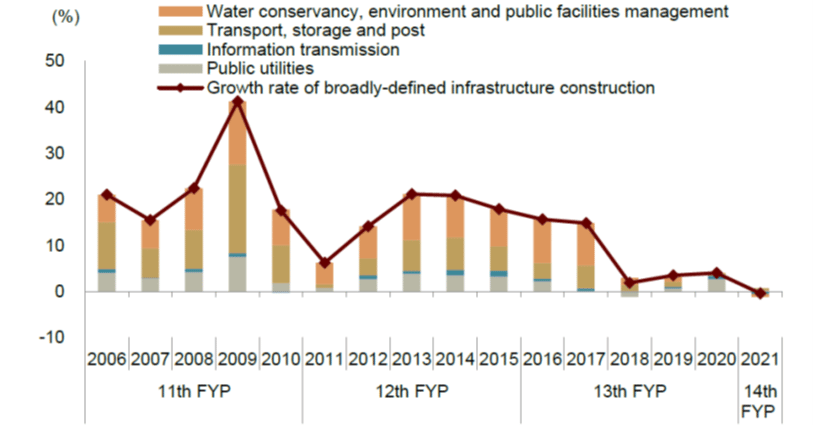

As it is, total China infrastructure investments in 2021 stood at CNY 13 trillion, which is a pale 0.2% year-on-year increase compared to the previous year in 2020 (see Figure 1). As such, expectations are for fixed asset investments to grow by between 6 to 8% this year in 2022. But of course, whether this is achievable depends on whether there is funding support for this spending.

Figure 1: Growth of infrastructure investments and sub-sector contributions

Source: Wind Information, 2022.

Where is the money coming from?

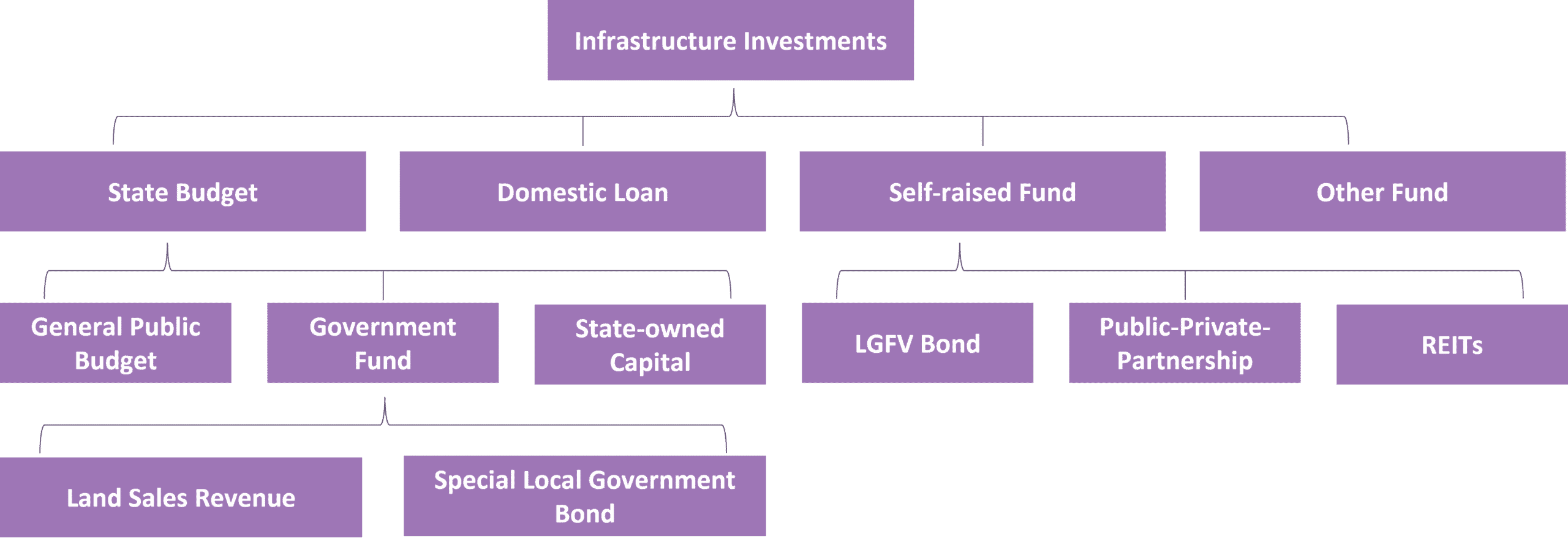

Briefly, the funding comes mostly from fiscal sources and social funds, namely the State and capital raised through bond sales. There are carried over funds to the government’s coffers from State-owned Enterprises (SOE) profits, revenues raised through land sales, transfers from the central bank, i.e. the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), and also monies raised through special local government bond sales (see Figure 2), that contribute to the bulk of the funding pool.

With the earmarked quota of RMB 3.65 trillion for 2022, and including proceeds raised from the sale of special bonds of more than RMB 1.20 trillion in Q4 2021, there is an estimated amount of c. RMB 4.8 trillion from special bonds-related funding to be employed this year. In addition to this RMB 4.8 trillion, local governments have raised c. RMB 2.6 trillion in bond sales in the first five months of 2022.

In short, there is funding available to finance China’s infrastructure-related projects and investments in 2022. Moreover, there are timelines on when earmarked quotas have to be utilised, so this may encourage and help front load spending on these infrastructure-related projects. Notwithstanding this, there could be some shortfall from land sales revenue amid the slowing property market backdrop, but there should still be ample funding overall – driven by the carry over and surplus funds from 2021, along with profit transfers from the PBoC, which is expected to support 2022’s overall fiscal spend.

Figure 2: Funding sources for China’s infrastructure investments

Source: Fullerton Fund Management, 2022

Infrastructure projects currently under way

China’s infrastructure investments have had a strong start in Q1 2022 and have remained resilient in the face of lockdowns in selected locations. Total infrastructure investments have risen 6.5% year-on-year so far in the January to April 2022 window, compared to the same corresponding period last year.

Separately, the bulk of the infrastructure spend thus far has mostly focused on energy capacity expansion (electricity production investments in power plants and power grid construction), railway extensions, as well as water conservancy projects, and expressway construction. Spending on these sectors are poised to grow relatively fast in 2022 under China’s 14th Five Year Plan.

Furthermore, while the attention now is on so called “old infrastructure” projects, the attention going forward is expected to shift dramatically to “new infrastructure” ventures involving upgrades in areas like high-performance computing, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and improved internet connectivity. Additionally, the infrastructure investments increasingly are expected to be in the towns and villages, rather than on the major cities as the rate of urbanisation slows.

Conclusion

In summary, infrastructure spending continues to be a key growth lever for China’s policymakers. It may not be employed in the same “bazooka style” manner of yesteryears, but it is still used in a measured way to support growth.

For 2022, there appears to be sufficient funding to finance the infrastructure project plans for the year. Coming off a flat infrastructure spend growth rate in 2021, the appetite for increased infrastructure-related spending this year is high, where activity could ramp up in H2 2022 especially in the wake of slower macro growth prospects.